Creating media outlets based on their own values, ideas and identity

Media leaders we spoke with during this research cited many reasons for starting their own news organisations. In this section, we explore some of their most frequently cited motivations.

Reasons for striking out on their own included:

- Not “finding their place” in traditional organisations

- A desire to be more entrepreneurial than they were permitted to be in legacy news organisations

- Wanting more freedom to cover the topics they chose, with their own vision

In our interviews with media leaders in France, Georgia, Luxembourg, Portugal and Turkey, we learned that many of them were inspired to set up their own news organisations in collaboration with other journalists after leaving more traditional media outlets.

The local digital news site Indip was co-founded by a group of freelance journalists in Sardinia, Italy in 2021 because they wanted more control over choosing what topics they covered, and how.

“Too many times, the editors-in-chief of national and local newspapers prevented us from developing a story in order not to annoy politicians or entrepreneurs,“ said Raffaele Angius, one of the site’s founders. “On Indip, by contrast, we are able to publish unheard stories, such as the presence of mafia organisations in Sardinia, or the corruption that affects our public administration.“

In Slovakia, Denník N was founded by a group of about 50 journalists who left a daily newspaper, after it was partially acquired by a group of new investors who had a history of being involved in corruption scandals with local politicians.

After starting its own website, the team went on to publish a new daily newspaper. The venture was named Denník N, because “N” stands for a Slovak word for “independent”, and they wanted to stress their independence from oligarchs and politicians.

The team at Denník N also produces a series of podcasts and video interviews, hosts political debates and related events, and publishes books. Since its launch in 2014, the outlet has become a significant contributor to Slovak political journalism and public discourse. Denník N has a reputation for being a liberal, pro-democratic, pro-European and progressive news outlet. After its success in the Slovak market, the same team of founders started a similar project in 2018 in the Czech Republic, with the name Deník N (both outlets are based on a subscription model).

Countering misleading marketing messages

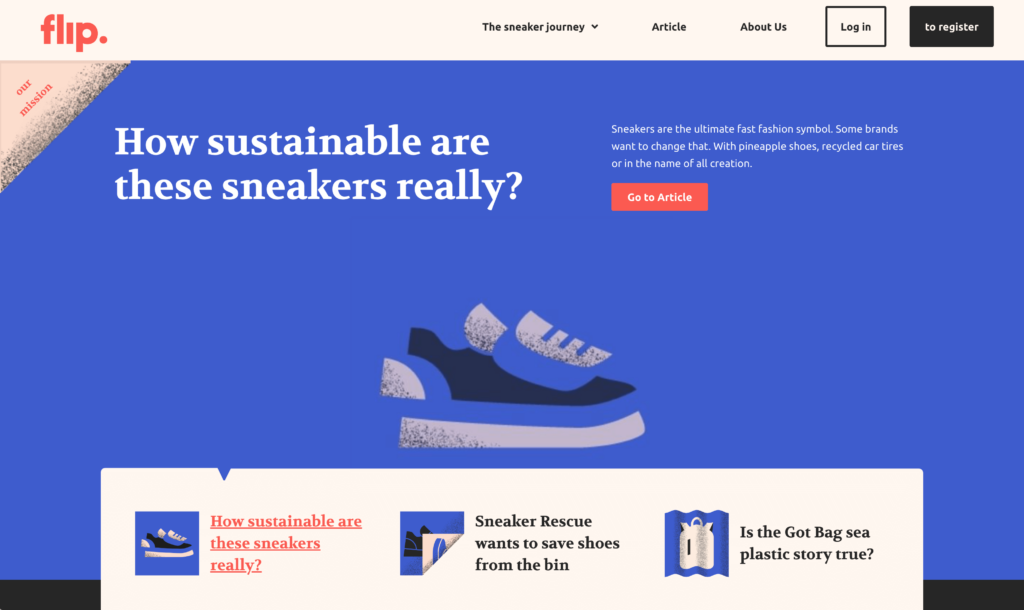

The news site Flip was founded in Hamburg, Germany, in 2020. Its mission is to help people to better distinguish between sustainable consumption alternatives and products they describe as “subject to greenwashing”.

In its bi-weekly newsletter, Flip provides in-depth, investigative reports on products and services that make sustainability claims. It then invites community members to rank the validity of these claims on a scale of 1 to 10. It aims to promote promising, impactful ideas and call out those who are not doing what they claim, with the goal of generating long-term impact on the environment, and informing the audience about misleading marketing messages.

One of its most in-depth investigations was on the recycling of sneakers, a project Flip undertook with two established media partners (the private Zeit and the public-sector broadcaster NDR). As part of their research, journalists tracked 11 cases, exploring whether sneakers were recycled. Their investigation found that many sneakers ended up in large dumps on the streets of Kenya.

After publishing the story, the team ran a crowdfunding campaign and raised €78,489 from 530 contributors to produce its own more environmentally sustainable sneakers. The co-production of genuinely sustainable alternatives to the products they review is one way the founders hope to continue financing their investigative work. To date, the media outlet has relied on crowdfunding, grants and start-up funds from angel investors.

Media leaders motivated by media capture

Qualitative data collected by our researchers in the country summaries suggests that more than 65% of the media included in this study exist in markets where media is controlled by a relatively small group of owners. These markets are typically dominated by large media players, and often heavily influenced by business and political leaders. Half of these countries also have government restrictions on media, and low press freedom rankings.

Our researchers found that in media markets where press freedom scores were low, digital native media often chose publishing platforms that made it easier to evade digital attacks and surveillance.

Research by Reporters Without Borders found that the Hungarian media market is dominated by the pro-government Közép-Európai Sajtó és Média Alapítvány (KESMA – Central European Press and Media Foundation), which owns approximately 500 national and local media organisations.

Yet despite the political, economic and regulatory pressures, we found independent digital native media in Hungary have had a significant impact — especially those who use social media to distribute content.

444.hu, established in 2013 by journalists who left the independent digital site Index.hu, quickly became popular with its distinctive “gonzo-style” journalism and mobile-friendly design.

When we completed our research at the end of 2022, 444.hu had more than 424,000 followers on Facebook, and more than 230,000 followers on YouTube.

In Turkey, which is often cited as a challenging media market due to political polarisation and government restrictions, many media leaders said they have opted for a social-first approach, avoiding publishing on a website altogether.

In almost all countries we studied that are known for having a high concentration of media ownership, fewer than 8.5% of the digital native media we interviewed reported advertising as their primary source of revenue.

In more than half of the 29 countries in markets with concentrated media ownership, we also found a high rate of digital native media practising investigative journalism, solutions journalism, explanatory journalism and fact-checking, often with a focus on covering human rights and environmental issues.

Establishing media in exile to counteract restrictions and provide crucial information

In countries such as Belarus and Azerbaijan, which are classified by Reporters Without Borders as having very serious limitations on press freedom, our researchers learned that independent digital native media founders often had to start their media organisations in exile. As a result of digital attacks and threats, they have often had to re-establish their news organisations, or find more discreet ways of publishing information.

In Belarus, many media outlets were labelled as “extremist” and some of their leaders were jailed during the 2020 protests there.

In the aftermath, many journalists fled the country to start new digital native media outlets, such as Pozirk and Zerkalo, which they have operated in exile ever since.

Pozirk publishes exclusively on Telegram to reach audiences without publishing information that can be easily searched for online. Established by the team originally behind news website Naviny.by, Pozirk continues the website’s tradition of objective, accurate and fast news reporting. The newsroom was based on the example of Belapan, Belarus’s first and only private news agency.

Naviny.by and Belapan were obliterated by President Aleksander Lukashenko’s regime in the aftermath of the 2020 protests. These outlets were branded “extremist”, and their key editors and founders are currently in prison. Members of those teams who managed to avoid arrest and flee Belarus created Pozirk as a news outlet in exile, and they said they chose Telegram as the sole distribution channel to get around the government’s attempts to block independent websites.

In our interviews, many of the leaders of independent media in countries with low press freedom scores reported that their work is often disrupted when their Facebook and YouTube pages are taken down because political leaders and others file false reports of plagiarism or other platform policy violations.

This practice has become so common around the world that the Electronic Frontier Foundation created a guide to appealing social media takedowns. But even if they are successful in getting their profiles and pages restored, digital native publishers face a difficult dilemma: each time they encounter these types of disruptions, they risk losing audience, brand awareness and the chance to build a reputation — especially when they have to set up entirely new organisations to counteract restrictions.

In SembraMedia’s 2021 Inflection Point Report on media in Latin America, Africa and Southeast Asia, digital attacks were reported as an increasingly common form of censorship and retaliation. More than half of the media leaders interviewed for that report said they had suffered cyber-attacks, ranging from hacked email and social media accounts to Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks.

Nearly 20% of the media leaders who reported these kinds of threats in Europe said they had been victims of online attacks or targeting.

Serhat News is an outlet founded by the non-profit organisation Dijital Medya Derneği (in English: Van Digital Media Association), covering Turkey’s eastern region in Turkish, Kurdish and English. The outlet is based in Van, a crucial passage point for refugees, primarily from Afghanistan and Iran, and covers migration, refugees and political issues related to the Kurdish minority.

Leaders of the Serhat News website said they face cyber-attacks on a regular basis, and that their journalists have been subject to physical violence on the ground. The newsroom has also received numerous lawsuits and police investigations. Despite these challenges, the founders said they are determined to continue publishing “to show everyone that journalism can be done despite the politics of intimidation”.

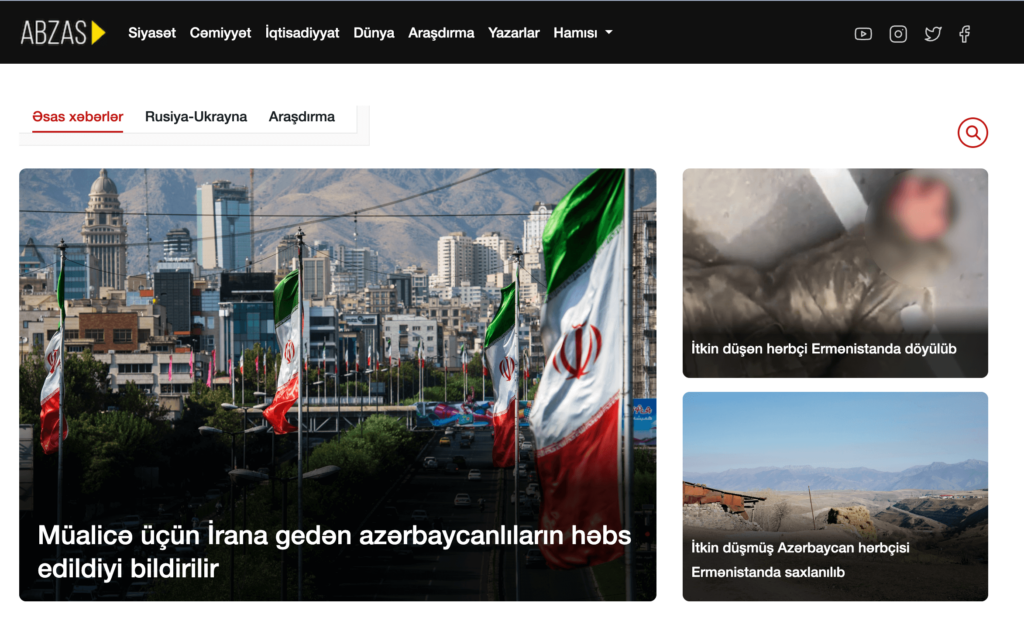

In Azerbaijan, Ulvi Hasanli, the co-founder of AbzasMedia, said that one of the main motivations for establishing the outlet was that in 2014, there were attacks on independent media in the country, as a result of which many media outlets were shut down. In light of these disruptions, in 2016 a group of journalists decided to create a new media outlet to fill the void and provide alternative news. They intended to highlight human rights violations, corruption cases and social problems.

However, as soon as the media outlet became popular, it faced severe difficulties. Its website domain name was blocked, and Hasanli was sent for compulsory military service. After he returned to civilian life in 2018, Hasanli discovered that “the media outlet operated only through proxy links, and its audience had decreased by 10 times“. AbzasMedia’s main web domain is unavailable in Azerbaijan, and the staff use another web domain to avoid restrictions.

Political polarisation is boosting demand for independent journalism

In Poland’s relatively diverse and independent media market, many of the digital native media leaders we interviewed said they were motivated to create their own media organisations to counter the increased politicisation of private media ownership, as well as buyouts of regional media by government-controlled companies.

Digital native publishers in Poland told our researcher that social media channels had proven the most effective way to generate website traffic. Polityka Insight and Kultura Liberalna have also developed podcasts to complement the reports on their websites. OKO.press has used a variety of multimedia formats to attract more than 136,000 followers on Instagram. In addition, most of the digital native media we included in Poland publish one or more email newsletters.

Motivated by concentrated media ownership

Our research shows that many media founders in this study were motivated by increasingly concentrated media ownership in their countries.

The founders of VierNull, founded in Düsseldorf, Germany in 2021, said they started their news site out of a motivation to counteract the increasing concentration of local news organisation ownership, and what they saw as a resulting reduction in coverage and quality. VierNull, which means FourZero in English, refers to the first two postcode digits of the publication’s target area.

Initially funded through a crowdfunding campaign, it now earns revenue primarily through subscriptions. As the founders started into their second year, they said they were exploring new ways to diversify revenue, including offering city tours to local residents and tourists.

VierNull’s founders added that their goal is to publish information that empowers Düsseldorf’s citizens to form their opinions and become more actively engaged with local political and community issues. In addition to publishing news on the website, the team sends subscribers a weekday newsletter at 5:30am, focusing on the main article of the day.

Filling information gaps and news deserts

In Denmark, Finland, Slovenia, Switzerland, the UK, Italy and Ukraine, many of the media leaders we interviewed said they were motivated to fill news gaps, cover underserved communities and combat mistrust and disengagement.

In Spain, the investigative news outlet Datadista “analyses in-depth issues that are under the radar of the traditional media,“ said founder Ana Tudela. The team prides itself on bringing to the news agenda issues that go unnoticed, such as environmental pollution from the expansion of chicken and pig farms.

In response to the Russian occupation of Donbas, Ukrainian outlet Svoi.City offers information for internally displaced people (IDPs), refugees and those who remain in occupied territory. Hayane Avakyan, journalist and coordinator of the organisation, said: “We helped our audience to navigate the ever-changing ‘rules and regulations’ of everyday life and possibilities to leave the area. As our team had to move to safer places, our mission became to help the audience to move as well.”

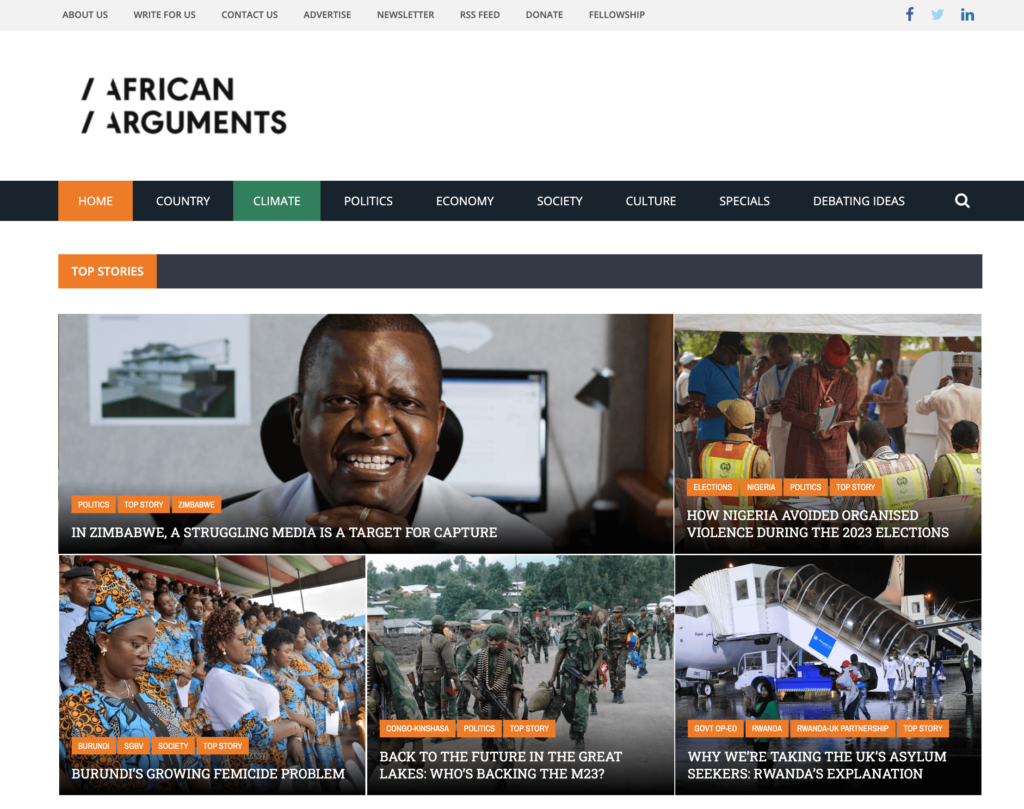

Leaders of the UK-based platform African Arguments said they were motivated to offer a counter-narrative to mainstream international coverage of Africa. Rather than focusing on the bad news often covered by foreign reporters, the newsroom produces and investigates stories that matter for Africans, amplifying a diversity of voices. Its goal is to raise awareness of the continent’s issues, with deep analyses, thought-provoking essays, open and informed debate and engaging original stories.

Challenges and opportunities in times of crisis

The Global Financial Crisis of 2008-2009, as well as the Covid-19 pandemic and the Black Lives Matter movement, have presented both challenges and opportunities for independent digital native media in Europe.

Anecdotal data collected by our research team, as well as quantitative data captured from our questionnaire, suggests that in several countries (including the Netherlands, Portugal and Spain) independent digital native publishers emerged — and even thrived — in the aftermath of these critical events.

Many of the media founders in this study said they were motivated to start their own news outlets to help make up for the loss of journalism coverage caused by budget cuts in more traditional media.

Nearly 17% of the media in our directory were established during the Covid-19 pandemic, most notably in Portugal, followed by Germany, Italy and Turkey.

Throughout the Covid-19 pandemic, digital native outlets found new opportunities to engage audiences with relevant content.

A report by the European Journalism Centre, published in April 2021, details the impact of funding provided to European newsrooms and freelancers at the start of the pandemic, and shows that many of these grant recipients were not only able to keep their organisations from shutting down, they increased audience engagement and participation.

Some 87% of these grant recipients said they were able to increase engagement with their communities through new initiatives or product offerings that extended their reach, often through non-digital channels. These included:

- Special print editions for elderly people

- Community response networks established to enable third-sector charities and other organisations to share information, resources and support with citizens

- Service desks and one-to-one advisory services to answer audience questions about Covid-19, and help them identify what subsidies and government support they qualified for

- Radio programmes addressing mental health and wellbeing during the pandemic

Mensagem de Lisboa is a local, community-based outlet covering the Portuguese capital city. Since its launch in 2021, it has worked hard to “create room to hear the voices of the people living in Lisbon”, said director Catarina Carvalho.

Mensagem is the only digital native media organisation in this study that publishes information in English in Portugal. It also translates articles into the Creole language to reach audiences of African descent living in Lisbon and its outlying areas. The news site organises newsroom meetings and tours around the city with readers, and publishes chronicles written by residents whom it has identified as underrepresented in other media (such as homeless people). Carvalho told our researcher they were also planning to start training young journalists from low-income neighbourhoods to help cover these communities.

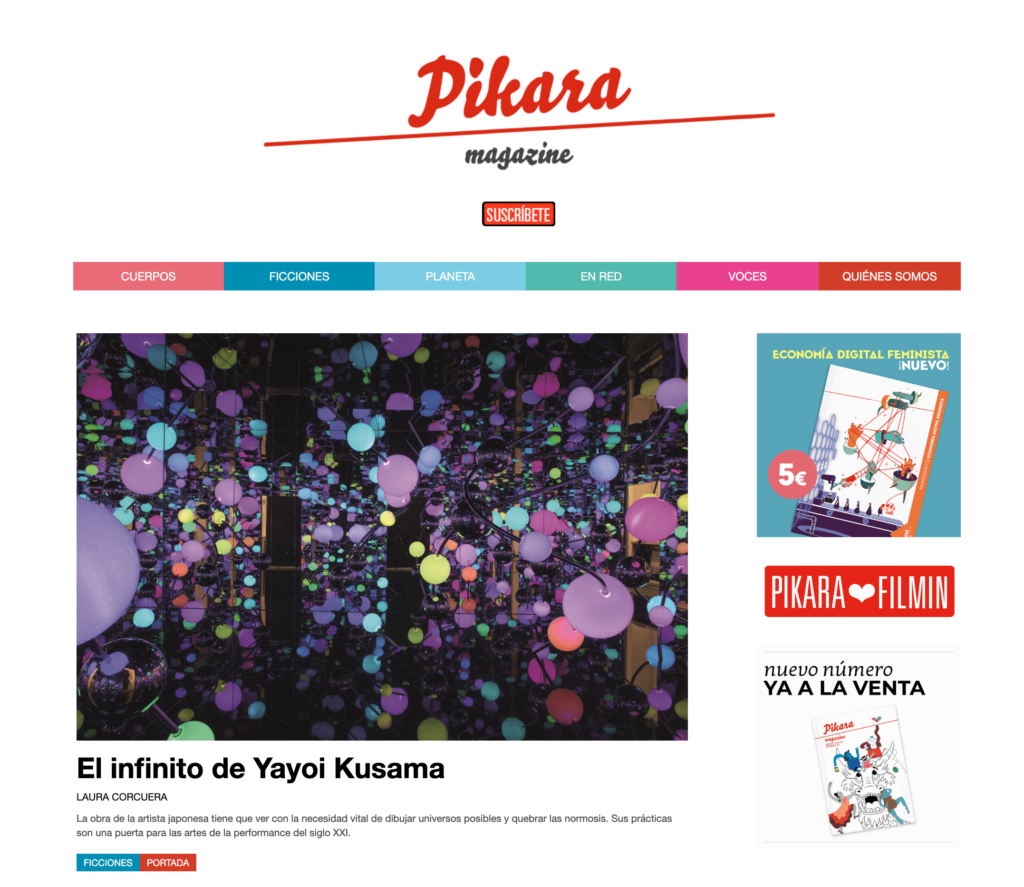

In 2010, two years after the economic crisis, four journalists from the Basque region in Spain founded Pikara Magazine, a non-profit outlet that covers political, economic, social and cultural issues from a feminist perspective.

Pikara Magazine primarily publishes information on its website. It also publishes a yearbook as well as four printed and three digital monographs annually, each of these focusing on a specific topic or trend. Its primary source of revenue comes from its 2,351 members. Nearly 40% of the Pikara audience visits the website from outside of Spain, primarily from Mexico and Argentina. In addition, the organisation receives revenue from the distribution and sale of printed publications, products such as tote bags, advertising and advisory services.

Pikara’s coordinator, Andrea Momoitio, said one of the most valuable lessons the team learned in its first 10 years was the importance of investing in the organisation’s management, planning and processes, besides content production. “You are always tempted to hire more journalists, but adding management team members has been fundamental for us,“ she said. The team has also learned that it’s vital to take breaks from publishing to focus on the organisation, she added. Every three years, the entire team stops publishing, and dedicates a month to strategic planning and reflection.

In some Southern European countries, the economic crisis and the Covid-19 pandemic were among the driving forces behind the launching of new independent digital native media. Across Central and Eastern Europe, disruptive political events were cited as one of the main reasons for the emergence of new digital native media in the last decade.

The Euromaidan uprisings in 2013, which created opportunities for greater media independence from government and oligarchs, led to an explosion of independent digital native outlets in Ukraine. The current war in Ukraine has forced most outlets to make changes to the topics they cover, as well as their frequency of publication and platforms used for their reporting. For example, increasing coverage of refugees and internally displaced people (IDPs), rolling or breaking news coverage, and the use of the Telegram messaging platform to send out direct alerts to readers.

A series of media captures in the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Poland, Bulgaria and Hungary in the last decade (2010-2020) left many journalists without a job. In those countries, our researchers found that some of these journalists went on to start their own independent media outlets, often making the leap from print publications to publishing online. Examples in our directory include Denník N, FORUM 24 and Telex.

Digital native media leaders in Slovakia told our researcher that journalists in the country were motivated to start their own publications after many of the more traditional media outlets changed from for-profit to “for-influence”.

In the Czech Republic, media leaders reported that news coverage changed dramatically after a wave of media capture in 2013. In reaction, some journalists created their own independent projects, and many moved from print to digital.

“It was a big change for me, I was always in print,“ said Pavel Šafr, the founder of FORUM 24 and a former editor-in-chief of leading media organisations in the Czech Republic, including Mladá fronta DNES, Lidové Noviny and Reflex magazine.