Bulgaria

Bulgaria’s online independent media outlets have been in crisis over the last few years amid the Covid-19 pandemic as well as a new law, the so-called Peevski Act (2018), which requires media organisations to register with the Ministry of Culture and to declare information about their sources of funding.

At least two media organisations – Belezhnik and Gabrovo Daily from Dobrich and Gabrovo cities respectively – have gone bankrupt and therefore halted their activities, despite the fact that they were among the most popular of Bulgaria’s regional media outlets. Other media organisations, such as Marginalia, are in difficult financial situations. Still others, such as Bivol, have faced SLAPPs (strategic lawsuits against public participation) which threaten their future potential to inform readers. Meanwhile, media leaders from bigger commercial outlets have complained of decreasing advertising revenue.

GENERAL INFORMATION

Press

freedom

ranking

Internet

penetration

POPULATION

Media organisations

in the Directory

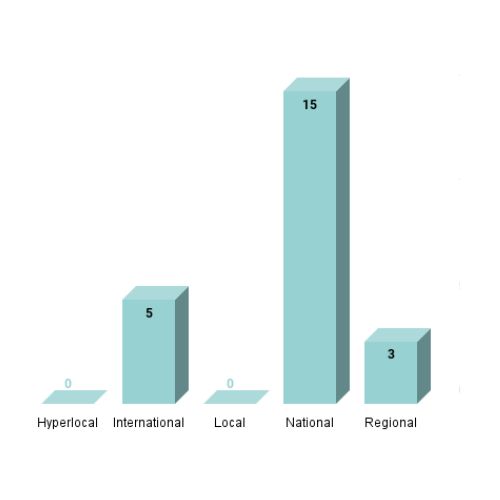

TYPE OF COVERAGE

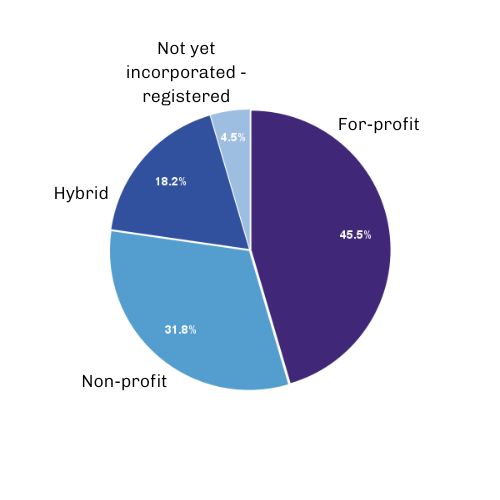

TYPE OF ORGANISATION

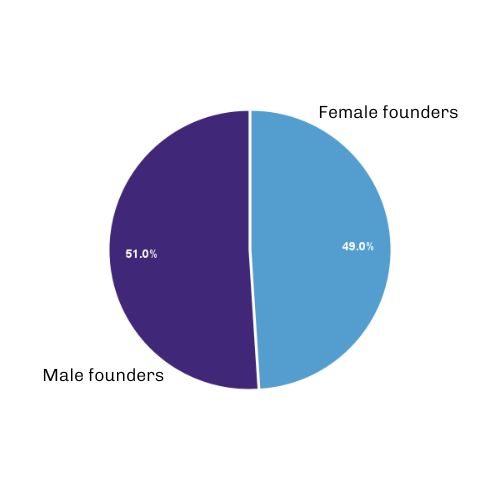

GENDER OF FOUNDERS

Press freedom

Bulgaria increased its position on Reporters Without Borders’ Press Freedom Index by 21 spots in 2022, moving to 91st place from its position at 112th the previous year. The country was considered as an example of “state capture” of the media between 2009 and 2021, because of the regime of former prime minister Boyko Borissov who served several terms as the country’s leader, and who has been accused of having ties with the mafia. His time in office was marked by a decline in media freedom, and certain media outlets “were used for exercising political influence”, notes Reporters Without Borders.

Under this regime, many media owners were accused of collaborating with the government and of self-censoring to avoid criticism or investigations of the Borissov government’s corruption. At the same time, Bulgarian officials have been accused of allocating European Union (EU) funding to media outlets loyal to the government.

A key figure during the Borissov era has been controversial media mogul and former lawmaker Delyan Peevski, from the political party DPS. Alleged media and financial collaboration between Borissov’s ruling party and DPS put the media sector under huge pressure; meanwhile, journalists investigating cases of corruption have accused media outlets linked to Peevski of orchestrating smear campaigns against them and their reporting. Peevski, who was sanctioned under the Magnitsky Act, stands accused of influence peddling and involvement in corruption.

Even after the Borissov era, the power of Peevski proxies is still a reality, with his influence said to extend from the media to the judiciary.

Market structure and dominance

The Bulgarian media market was badly affected in 2009 after the major financial and economic crisis. Leading investors in the Bulgarian media industry such as Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung and News Corp were leaving the market, and media moguls such as Peevski were actively acquiring these media outlets from them, accumulating influence.

Over the past few years, Bulgaria has also been criticised for a too-explicit monopolisation of the media sector, with oligarchs affiliated with the government trying to buy more and more media outlets, often resulting in the closure of these outlets and the firing of their journalists.

The Bulgarian media sector is under attack, as was highlighted in the 2022 annual research report on press freedom in the country by the Association of European Journalists-Bulgaria. In November 2022, another strike against independent media outlets was made by the leader of pro-Russian ultra-nationalist party Vazrazhdane, Kostadin Kostadinov, who proposed a bill similar to Russia’s notorious “foreign agent” law, involving potential sanctions for media organisations that receive funding from abroad.

Over the past two years, protests in Belarus, Russia and Kazakhstan, as well as Russia’s hybrid war in Ukraine, have also brought up a new trend – Bulgarian media outlets have started to create channels on the messaging app Telegram, which is popular in post-Soviet countries. In addition, the war in Ukraine brought Ukrainian television to Bulgaria; some telecommunication providers have included Ukrainian TV channels in their packages.

Twenty-three profiles of digital native media organisations from Bulgaria are included in the directory.

Several outlets, including Fakti, Actualno and OffNews, are real examples of financial success; after five to 10 years of hard work, they have increased the number of employees in their newsrooms, the number of websites in their media groups and advertising income. Another organisation, Boulevard Bulgaria, is financially successful after just two years of activity. These outlets’ readerships, revenue from advertising and total financial revenues are mostly rising.

A widely mentioned issue from the media leaders, founders, owners, publishers and editors-in-chief interviewed for Project Oasis is the so-called Peevski Act, which is seen as “killing” crowdfunding and donations campaigns.

In addition, a rise in SLAPPs in 2021 saw lawsuits brought against news outlet Mediapool (its former reporter Boris Mitov was fined €30,000 regarding coverage of a top magistrate) and Bivol (the outlet was sued for a record €0.5 million by one of the country’s leading insurance companies).

Those interviewed for Project Oasis also mention the Covid-19 pandemic and war in Ukraine as huge issues affecting the media market, leaving them no chance to grow. This lack of financing and advertising has led to more and more media outlets introducing donation buttons to their websites. Increasingly, media outlets in Bulgaria are adding links to Patreon and other platforms for crowdfunding and donations to their standard social media kit.

For their part, Fakti and Actualno say they do not take grants, because their owners are oriented towards financial and editorial independence, which they believe can be gained through selling advertising and services while avoiding collaborations with donors.

A decrease in the ratings of the major TV channels in Bulgaria has given a chance to independent media organisations, their podcasts and their YouTube channels. Due to censorship and political influence over public service broadcaster Bulgarian National Television, several of the best TV journalists were kicked off Bulgaria’s main channel. Some of them went on to work for private TV channels, while others started new projects online, as with the Alternativata YouTube channel, which is financed by viewers’ donations. Meanwhile, the Covid-19 pandemic and Russia’s war in Ukraine have also led to media outlets in Bulgaria starting to integrate fact-checking rubrics into their reporting.

A decrease in the ratings of the major TV channels in Bulgaria has given a chance to independent media organisations, their podcasts and their YouTube channels. Due to censorship and political influence over public service broadcaster Bulgarian National Television, several of the best TV journalists were removed from Bulgaria’s main channel. Some of them went on to work for private TV channels, while others started new projects online, as with the Alternativata YouTube channel, which is financed by viewers’ donations. Meanwhile, the Covid-19 pandemic and Russia’s war in Ukraine have also led to media outlets in Bulgaria starting to integrate fact-checking rubrics into their reporting.

Last updated: January 2023

CREDIT FOR STATISTICS: Press Freedom statistics, RSF Press Freedom Index 2022; Internet penetration and population statistics, from Internet World Stats