Czech Republic

The media landscape of the Czech Republic changed dramatically after incidents of media capture and control in 2013. As a result, some journalists created their own independent projects and many moved from print to the digital space. Newly established media outlets have struggled financially and have had to look for new sustainability models.

GENERAL INFORMATION

Press

freedom

ranking

Internet

penetration

POPULATION

Media organisations

in the Directory

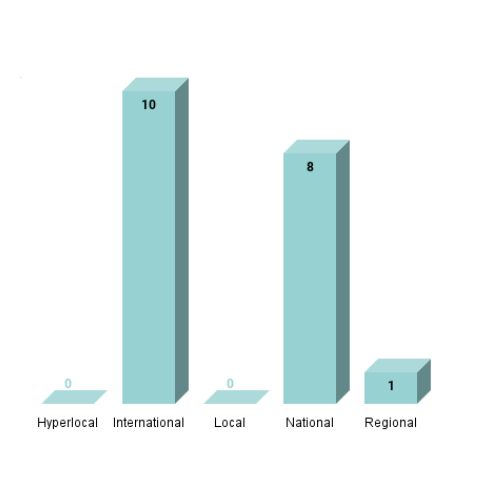

TYPE OF COVERAGE

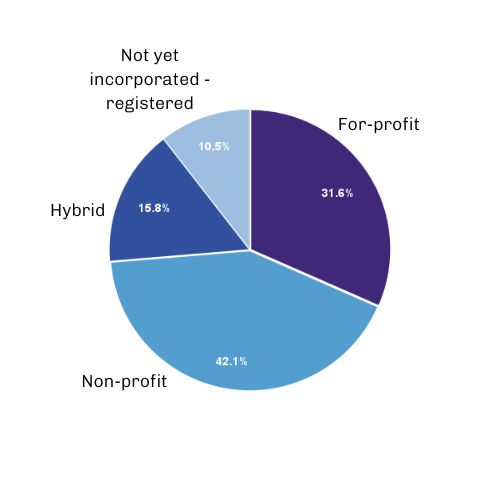

TYPE OF ORGANISATION

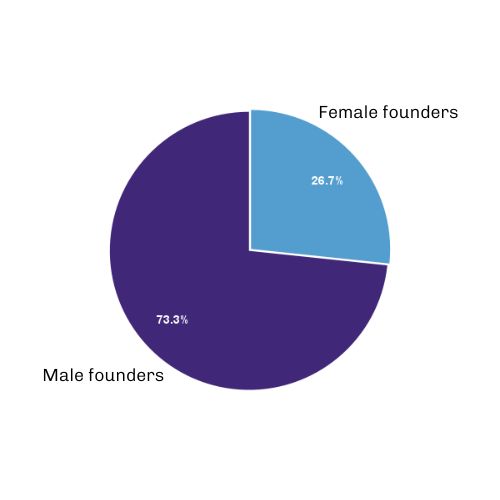

GENDER OF FOUNDERS

Press freedom

As Reporters Without Borders notes in its Press Freedom Index, the Czech Republic’s media landscape is characterised by “significant concentration of large media groups in the hands of major economic players”, including the country’s former prime minister Andrej Babiš.

In 2013, the country’s biggest media house, MAFRA (publisher of the influential newspaper Mladá fronta DNES and the country’s oldest newspaper Lidové noviny), was bought by the billionaire and politician Babiš of the ANO political party. Dozens of journalists had to find a new job after this.

“Media capture is a strategy employed purely for ‘electoral purposes”, to ensure that the media outlets help to ensure the elections are won,” says Marius Dragomir, director of the Media and Journalism Research Center at University of Santiago de Compostela. Babiš subsequently went on to serve as the country’s prime minister from 2017 to 2021.

Meanwhile, at the end of 2013, Daniel Křetínský and Patrik Tkáč (of the Czech News Center media house) bought the weekly magazine Reflex and the tabloid Blesk, owned by Ringier Axel Springer. Since 2019, Křetínsky has also held a minority share of French daily Le Monde.

In terms of journalist safety, a significant incident was the 2018 murder of Slovakian journalist Ján Kuciak, who was shot dead in his home. Czech journalist Pavla Holcová, who had been working with him, was subsequently put under police protection.

Market structure and dominance

The Czech media landscape is characterised by strong radio and television networks, including the main public service broadcaster Česká televize and Český rozhlas (Czech public radio). However, Český rozhlas has faced attempts of capture or censorship of content, adding to pressures imposed on journalists and editors.

Since 2013, there has been a growing number of independent digital projects and podcasts in the Czech Republic. Some of these are being incorporated into established media houses. One of the most expansive media projects is Seznam zprávy, founded in 2016. Seznam zprávy has the unique position of being part of the company Seznam, the competitor of Google in the Czech Republic. In terms of print media, one leading publication is the monthly magazine Reportér, founded in 2014 by its editor-in-chief Robert Čásenský, who used to be the editor-in-chief of Mladá fronta DNES.

How media is funded

In 2016, the NFNZ (Endowment Fund for Independent Journalism) was founded to support independent journalism in the wake of the concentration in ownership of media titles in the country. The goal was to support investigative journalists who have been affected the most, but such media capture has also crucially affected other strands, such as foreign reporting and coverage of the economy.

Journalism in the Czech Republic is generally underfunded. Organisations that are not backed by a media house (like Economia or Seznam) have to rely on a mix of grants and the support of their readers. In 2021, the Association of Online Publishers was founded. Its aim is to lobby the authorities of the Czech Republic and the European Union in favour of independent media, in the form of financial support and preservation of freedom of speech. They strive for a dialogue with technology platforms about rules for publishing content and limiting publishers’ advertising.

Nineteen profiles of digital native media organisations from the Czech Republic are included in the directory.

The media landscape in the Czech Republic grew turbulent in 2013 after a series of media captures, and this led to the emergence of new digital media organisations. “We strongly believed the politician should not own the media,” says Dalibor Balšínek, the former editor-in-chief of Lidové noviny.

In March 2014, Balšínek launched Echo 24, which was based on the cheapest but most profitable of content types – opinion. Echo 24 targets conservative readers. A printed weekly magazine was launched soon after. Later on, its publishing house was launched, and the online newspaper became more of a marketing tool to promote magazines and books; print again became a vital part of the project.

Echo 24 was followed by Hlídací pes, founded in April 2014 by Ondřej Neumann. This project is focused on investigation, and stays digital. It publishes books as well, but its print offerings, in contrast to Echo 24, are meant as a marketing tool.

In 2015, the digital Svobodné forum was established. “It was a big change for me, I was always in print,” says Pavel Šafr, who was a former editor-in-chief of leading media titles in the Czech Republic such as Mladá fronta DNES, Lidové noviny and Reflex magazine. Svobodné forum was an opinion daily. In 2017, it was renamed Forum 24 and became a news site. Today, there is also a print edition, Weekly Týdeník Forum.

And amid the “male world of the Czech media landscape”, Pavla Holcova, who previously worked in the non-governmental organisation sector, founded Investigace.cz in 2013. Her project gained a reputation for following international corruption cases. Investigace.cz is part of the OCCRP network. Holcova based her financial model on a mix of reader support and grants; she does not intend to put content behind a paywall, as she prefers to have information publicly accessible.

Meanwhile in 2016, Seznam zprávy was created under the umbrella of the company Seznam, the competitor to Google in the Czech Republic. The site is expanding and hiring investigative journalists, mostly from former MAFRA titles. It has recently become one of the most powerful media houses in the Czech Republic. Its revenue comes from advertising.

Another organisation featured in the directory, Deník N, was created in 2018. Contrary to other digital media outlets, it bet on the paywall. “For us it was always digital first. Print has no future,” says the director of Deník N, Ján Simkanič. Print and books help more or less as tools for marketing the daily, but digital content is financially important. Deník N makes use of newsletters, and reporters are encouraged to promote their work on social media.

In contrast, the Deník Referendum digital media outlet, which was established in 2009, has the following slogan: “No oligarchs, no paywall. Just your donations and our work.” Editor-in-Chief Jakub Patočka came up with a unique source of income: “The readers who wish to debate under the articles pay a fee. This approach generates a modest income and also helps cultivate the discussion.”

Huge upheaval to the media landscape in 2013 struck a blow to journalism in the Czech Republic. For many journalists, this marked the beginning of a struggle to stay in the profession. But many proved resilient, and in the end a new, diverse media landscape emerged. Most content moved to the digital space; unfortunately at the same time, disinformation grew similarly prevalent.

Traditional media organisations have thus been replaced by new, but not always transparent, sources of information. For readers, it is sometimes a challenge to figure out which outlets are based on hidden advertising, which are spreading disinformation, and which produce solid journalism.

Last updated: January 2023

CREDIT FOR STATISTICS: Press Freedom statistics, RSF Press Freedom Index 2022; Internet penetration and population statistics, from Internet World Stats