France

Independent news media outlets in France are developing in an environment of strong concentration of the press, which continues to be absorbed by a handful of billionaires, families or companies, and where private opinion media outlets compete strongly with information media organisations, also monopolising a significant part of the public funds intended for media development.

GENERAL INFORMATION

Press

freedom

ranking

Internet

penetration

POPULATION

Media organisations

in the Directory

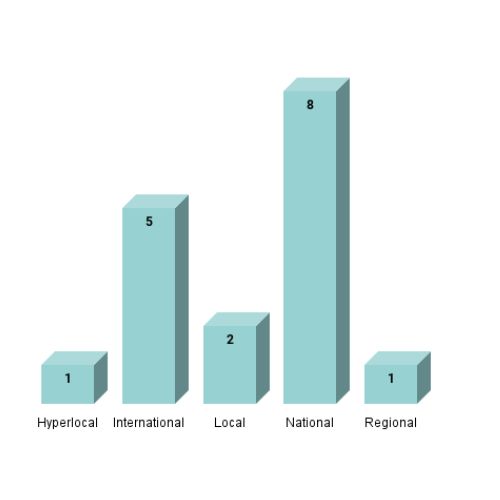

TYPE OF COVERAGE

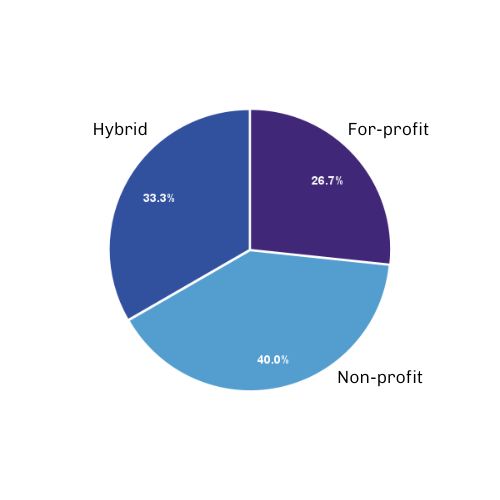

TYPE OF ORGANISATION

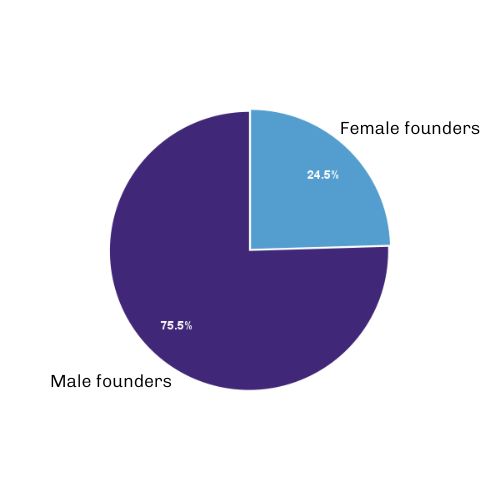

GENDER OF FOUNDERS

Press freedom

Press freedom in France has had an upturn in 2022, explained by a relative appeasement after the difficult period experienced during the “yellow vests” movement (which began in 2018), during which police violence extended to the press. Several media outlets interviewed for Project Oasis spoke about this violence and police actions that have become recurrent, especially during coverage of street protests (during which journalists have been beaten or taken into custody without reason).

It is not uncommon for media outlets or journalists to be subjected to SLAPPs (strategic lawsuits against public participation), mainly brought by entrepreneurial groups. A recent case is the referral of the Altice Group against the media outlet Reflets.info, which resulted in a ban on the media organisation from continuing to publish investigative articles about Altice, because of the infringement of business secrecy. According to the Spiil (union of the independent online press), the decision effectively establishes censorship, a situation already observed and reported by the union since the entry into force in 2018 of the country’s law on the protection of business secrecy, a law that aims to ensure, for the benefit of companies, the protection of information with commercial value.

Market structure and dominance

Public and private broadcasting hold an important place in the French media ecosystem (public broadcasters include France Télévisions, Radio France, TV5 Monde, l’INA, France Médias Monde and the Franco-German TV channel ARTE, while private broadcasters include TF1, Canal+, C8, W9, TMC, BFM TV, CNews and so on), characterised by a large concentration of media outlets by big corporations, a situation that has become so important that the French Senate has launched a commission of enquiry on the subject.

On the other hand, the distribution of print media remains important. The printed newspapers with the largest circulation are Le Monde, Le Figaro, L’Équipe, Les Echos and Libération, and numerous magazines and special issues fill the newsstands every week.

In parallel, many independent media outlets are emerging regularly, developing mainly online. Most of them are members of the Spiil (created in 2009), which on 31 December 2021 had 261 members, representing 314 general and specialised press organisations, thus making it a leading press union.

Additionally, in 2019, Ouest Medialab carried out research that aimed to map local news media organisations in France. Exploring various sources, including the Spiil member database, the study identified 1,512 local newsrooms across radio, TV, print and digital native media.

How media is funded

The main sources of revenue for media outlets in France are subscriptions, newsstand sales, advertising and public grants, as well as the organisation of events, the sale of derivative products and the establishment of partnerships. Currently, there are fears about public subsidies to the press, after the announcement of the abolition of the public broadcasting contribution (a contribution that all television owners had to pay, except in certain cases). This measure was taken by the government in 2022 as a “measure in favour of household purchasing power“, but could have an impact on media funding and harm media pluralism, especially since the situation is already not favourable to small- and medium-sized media outlets, as the biggest media outlets, owned by billionaires, monopolise most direct state funding.

Seventeen profiles of digital native media organisations from France are included in the directory. This includes 11 profiles based on interviews and six profiles based on desk research.

What characterises the media outlets interviewed is their strong commitment to creating organisations with a pronounced identity that differentiates them from the main press titles, and a strong claim to their financial independence, as well as to their independence from any political or economic power.

This media ecosystem is remarkable for its dynamism (new titles appear regularly), diversity and variety of subjects. Many of these publications were created as a result of a lack of accurate information on certain important subjects, a lack of representation of some communities, as well as a desire to talk about subjects considered to be insufficiently covered by traditional media organisations, such as ecology, disability issues and information on specific regions of the world that are poorly known by both journalists and the public.

There is an observable rise in audio formats (podcasts) and in explanatory journalism with the aim of contextualising facts, verifying data, talking about certain social groups in a more accurate way, giving necessary importance to certain subjects that are essential to understanding the complexity of the current world (such as environmental issues), but which are minimised or stifled by the overall media noise and by the impoverishment of the quality of information.

There is also a strong desire to produce investigative journalism, even if this requires a large investment – of both financial and human resources – that not all media outlets have, which strongly limits their development.

In addition, the research has found that newsletters have become a very popular tool for building a closer relationship with readers and for curating articles on specific topics.

Regarding funding, the main sources of revenue for digital media outlets are subscriptions, public grants, services provided to other media outlets or enterprises, and media education.

Some of the most important independent online media outlets have been created by journalists following a redundancy, or by those who left a traditional publication whose functioning did not suit them anymore, especially after the organisation was bought by private companies. Often, the initial investment to create their organisations comes from the founders’ own funds and the voluntary work of the journalists.

In France, in addition to non-profit and for-profit organisations, there is a special status for the political and general information press, created in 2015 after the Charlie Hebdo attack to promote the development and economic viability of the independent press. Inspired by the social and solidarity economy, this status requires the reinvestment of at least 70% of annual profits in the company, and prohibits the acquisition of any stake by a third party.

Another particularity of this media ecosystem is its collaboration. For example, some media outlets have started to share workspaces that facilitate the creation of common projects and reduce costs. Initiatives such as a newsletter by the outlet Basta!, which provides a weekly selection of articles in different formats from 138 independent media organisations, show the solidarity between these publications, which are becoming more visible and accessible to internet users. The Free Press Fund, a non-profit organisation whose aim is to defend freedom of information, press pluralism and independent journalism, and which was created in 2019 on the initiative of Mediapart, is also an expression of this solidarity.

Citizens play an important role in the survival of the independent digital media sector, as they are the main funders, subscribing, donating and supporting publications when they are subjected to SLAPP suits.

An important thing to mention is the interest that independent media organisations have in training future journalists, and in opening journalism to people with diverse profiles. This responds to the observation made about the lack of representation of certain social groups, which can be partly solved by integrating people from different backgrounds and cultures into editorial staff.

Finally, ecological topics have become important concerns for the media in France. Last September, the media organisation Vert launched a charter for a journalism at the height of the ecological emergency to contribute to improving media coverage of environmental issues; to date, around 1,200 journalists and dozens of newsrooms and journalism schools have signed it.

French independent online media outlets have learnt that there is strength in numbers, and that together, they can encourage necessary changes in journalism that would be hard to come by in traditional media organisations. The initiatives mentioned previously are part of the independent media sector’s quest to make a stand against the traditional press, and to act against media concentration and the difficulty of obtaining funding that would allow them to be viable in the long term. The large number of Spiil members is proof of this desire to establish a common front to face the current common challenges.

What remains to do is to foster a more favourable environment for press freedom, one that ensures its long-term sustainability, protects it from attacks by private interests, and ensures the safety of journalists in the course of their work.

Last updated: January 2023

CREDIT FOR STATISTICS: Press Freedom statistics, RSF Press Freedom Index 2022; Internet penetration and population statistics, from Internet World Stats