Romania

The Romanian media landscape is relatively diverse, and follows a global trend of decreasing print media outlets and growing online media outlets.

However, the emergence of new media organisations has been severely hampered in the last few years, especially in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, when public distrust in the media soared. Romanian independent media publications are facing serious financial hardships and are generally struggling to self-sustain, with limited support from public and/or privately-owned companies. As a result, some media organisations have had to reduce staff and/or find cheap or free ways of distributing content, such as Telegram channels or email newsletters.

Most media outlets are concentrated in the capital, Bucharest, and a few other big cities. Local press is tiny and struggling, largely dependent on local barons accused of buying positive public representation during elections.

GENERAL INFORMATION

Press

freedom

ranking

Internet

penetration

POPULATION

Media organisations

in the Directory

TYPE OF COVERAGE

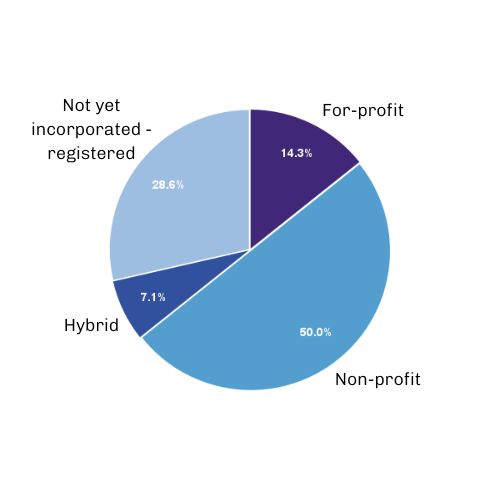

TYPE OF ORGANISATION

GENDER OF FOUNDERS

Press freedom

Press freedom in Romania is suffering severe setbacks, due to financial struggles and the growing distrust of the public, especially in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Although press regulation is aligned with European Union (EU) standards, the protection of the freedom of the press and access to information is insufficiently enforced. Journalists habitually face challenges in obtaining information from public institutions, despite FOIA (Freedom of Information Act) legislation. Some institutions use GDPR (the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation) to justify denying journalists access to information that would serve the public interest.

SLAPPs (strategic lawsuits against public participation) are on the rise, and journalists are also facing online harassment, threats and even physical abuse. For example, PressOne journalist Emilia Sercan received anonymous death threats from a police officer after uncovering plagiarism by the chief of the Police Academy. Another example is that of a reporter, a filmmaker and an activist who were badly beaten up while documenting illegal logging for the Recorder media outlet.

Public radio and television heads are politically nominated, and their editorial policies are often subservient to the political party currently in power. The biggest privately owned media outlets are not transparently funded. Most are owned by businessmen with direct political interests, which reflect in the coverage of the media.

Fourteen profiles of digital native media organisations from Romania are included in the directory.

Independent media outlets are struggling financially. These organisations are understaffed and heavily rely on freelancers to produce content. This creates a precarious working environment for journalists, who often have to choose between making a decent living in a bigger, but corrupt, media outlet, or financially struggling with uncertainty and inconsistency in the independent media sector.

The predominant sources of revenue for independent media organisations are grants from charities or private companies, together with individual contributions from the public, crowdfunding campaigns and native advertising.

Some organisations use a combined business model, having several sources of revenue, while others rely exclusively on donations from the public and crowdfunding campaigns as a way to ensure complete editorial independence and no external influence.

However, media leaders report that the latter model is inconsistent and creates stress for journalists. They report gaps in financing, as well as other issues related to grants. “We can apply for funding, but the programmes of NGOs or EU institutions will only finance stories on a particular topic. The problem is that in a small newsroom, journalists have to cover a variety of topics, not just one in particular. We can get access to money for a particular story or theme, but not for the newsroom as a core business,” says Adrian Mihaltianu, the editorial director of PressOne.

A few of the outlets interviewed rely on private funding from a bank to finance their operations. Even if the bank grants full editorial independence to the media outlet, there is still the issue of depending on a single revenue source. “We have a privileged position because [the bank] is giving us money to write about whatever we want. But every day we have this fear that they will stop the financing if business is not going well for them,” says Ioana Pelehatai, the editor of Scena9.

Notably, most media organisations interviewed have expressed a need to rely more on individual donations and crowdfunding, rather than grants and advertising. Few of them have managed to build a constant stream of donations, which limits their capacity to employ more journalists and explore important topics for the public. Most report that journalists are struggling with burnout and mental health issues, especially since the start of Russia’s war in Ukraine.

In terms of content delivery, there are some developments that mirror global trends: media outlets are trying to produce more video content, rather than written content. There are also a few podcast initiatives that are moderately successful. Social media plays a key role for most of the media outlets interviewed. Most of their website traffic comes from Facebook, the main social media platform in Romania. However, reach has been steadily decreasing over time, so some newsrooms have found a solution in developing newsletters (for example, Concentrat, a Decat o Revista product).

Some media outlets are entirely reliant on social networks. For example, Gen, stiri emerged recently as a response to young people not accessing news through legacy media, but rather through social media and memes. Gen, stiri produces content exclusively for Instagram and TikTok, where its audiences – teenagers and young adults – spend their time online. Similarly, Casa Jurnalistului has narrowed its activity to produce content specifically for its Telegram channel and Instagram stories. However, this makes it vulnerable: “Any change of the algorithm can negatively affect the project,” says Teodor Tita, editor of Gen, stiri.

Very few new media outlets have emerged in the last few years, especially since the Covid-19 pandemic. The independent journalism scene itself is quite small, with just a few people getting involved in several projects. There are few young journalists joining independent media outlets, while some seasoned ones are leaving, searching for better opportunities in other fields. Recently, Decat o Revista, one of the oldest independent media outlets in Romania, announced its closure due to financial hardship. This has been mentioned by a few of the media leaders interviewed as dire and demoralising news.

The Romanian independent digital media sector “is not disappearing, but it’s not flourishing either”, says Adrian Mihaltianu, editorial director of PressOne. “Clean” journalism is underfunded and competes with a much more powerful mainstream media, which is accused of serving political interests and even leading disinformation campaigns. Almost all independent newsrooms could benefit from more financial contributions from the public, but there is a limited category of the population with the means and interest to donate. Independent newsrooms have to find creative ways to finance their work and livelihood, but energy and enthusiasm are low.

Last updated: January 2023

CREDIT FOR STATISTICS: Press Freedom statistics, RSF Press Freedom Index 2022; Internet penetration and population statistics, from Internet World Stats