Turkey

Turkey is a key example of a case in Europe where independent journalism and innovation have endured repression for at least a decade. Independent newspapers and magazines are going through a digital transformation, with the emergence of multimedia platforms launched by seasoned journalists in recent years. Editorial content mostly responds to day-to-day developments in politics and the economy, with a strong inclination towards opinion, whether through written columns or video.

Business models heavily rely on grants from international philanthropic organisations, since advertising and audience support cannot constitute sustainable revenue sources. YouTube has emerged as the main platform for newcomers, offering the advantage of working as a video content studio to generate revenue and higher engagement among younger audiences.

GENERAL INFORMATION

Press

freedom

ranking

Internet

penetration

POPULATION

Media organisations

in the Directory

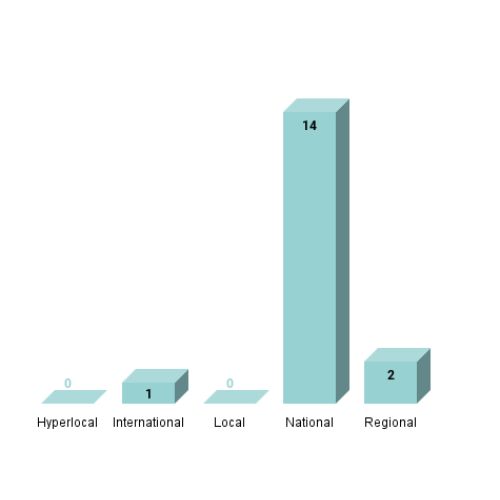

TYPE OF COVERAGE

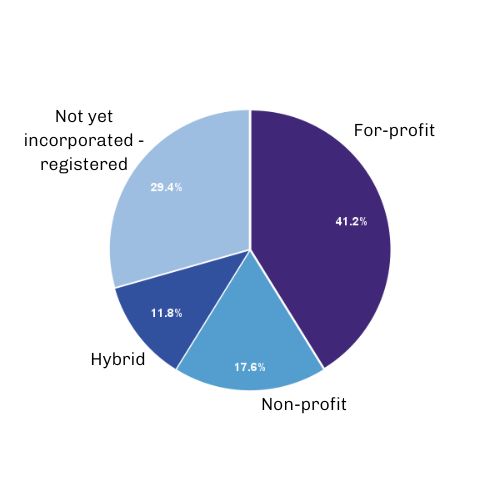

TYPE OF ORGANISATION

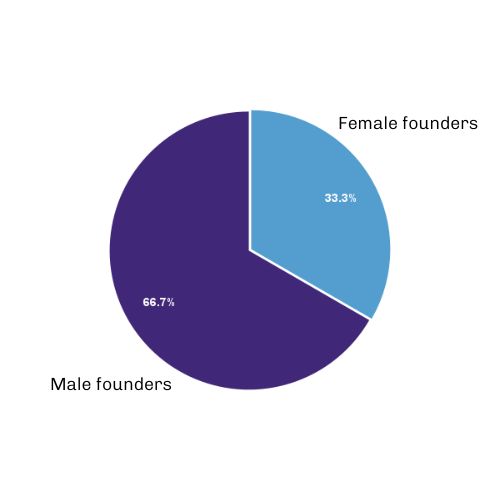

GENDER OF FOUNDERS

Press freedom

Calling Turkey’s media environment difficult would be an understatement. Incidents of media capture and the tight control of state authorities over once-legacy print and TV newsrooms are well documented (see the Columbia Journalism Review, Reuters). As a result, independent outlets constitute an overall attempt to build an alternative media ecosystem from scratch to counter pro-government media organisations. Amid a market structure shaped by the government’s will, media companies committed to doing quality journalism face considerable setbacks in building sustainable business models to ensure independence.

According to data from the Committee to Protect Journalists, 40 journalists are imprisoned in Turkey as of December 2022. In 2021, 545 journalists stood trial, often targeted by SLAPPs (strategic lawsuits against public participation) to hinder the public’s right to information, according to Justice for Journalists. One interviewed media leader puts it bluntly: “Every journalist in Turkey self-censors to varying degrees.”

Seventeen profiles of digital native media organisations from Turkey are included in the directory.

A generational divide defines independent media leaders. Multimedia news platforms launched by former legacy media journalists face difficulties in aligning editorial output with a sustainable business model. In contrast, digital native players, some of whom view themselves as media entrepreneurs, prioritise engagement metrics and vertical formats to generate revenue as content studios. Even though female editors and directors are employed, female founders are extremely rare.

Recently launched media outlets have adopted a social-first approach, avoiding publishing on a website. Many media leaders have voiced concern that despite soaring social media engagement, website page views have recorded a steady decline over the last few years. Short-form documentaries and explainer videos on YouTube, in addition to graphics-heavy posts on Instagram, are emerging as a more sustainable way to quickly build an engaged audience. TikTok is a platform of growing interest for engaging the population under the age of 24 (nearly 13 million).

The outlets’ dissemination strategies involve various social media platforms, for different reasons. Some organisations use Discord for casually engaging audiences, while livestreaming on Twitch, Instagram and YouTube is also gaining ground. Semih Sakallı, co-founder of the Mesele Ekonomi YouTube channel, highlights the importance of LinkedIn, which enables direct connection with potential advertisers.

Grant funding is the primary means of support for independent media. Most of the organisations are only able to continue operating because of revenue provided by international philanthropic donors. For example, European Endowment for Democracy grants are a crucial lifeline in building, launching and sustaining digital native media outlets.

One media leader, who asked not to be named, says straightforwardly: “Without grants, none of the independent media organisations can survive here.” Heavy reliance on grants keeps most of the organisations financially afloat, yet some of them are under constant attack, framed as “foreign agents” or as acting on behalf of other countries’ interests.

Another media founder denounces the “black propaganda” around grant funding, elaborating on why his organisation has chosen not to make public the names of its donors. The overwhelming majority of media organisations from Turkey included in the directory do not publish information about their team and revenue sources, due to long-sustained intimidation campaigns both online and offline. Some media leaders say that although they were not very keen to do so initially, they eventually applied for grants to increase their number of full-time employees or to buy technical equipment. In future projections, almost all the organisations strive to lower their percentage of grant funding.

Meanwhile, political polarisation is a considerable challenge for community-driven journalism, as organisations fret over limiting their outreach to a specific demographic. The economic downturn in the country makes it very difficult to sustain audience revenue. “In order to ask money from the audience, one has to offer very fulfilling content, which is very hard to achieve without an expanded team and investment,” says Şükrü Oktay Kılıç, founder of Fayn Studio. YouTube channel membership is the most common membership model, while crowdfunding on Patreon has also been a revenue stream for some.

Content strategies focus on immediate coverage of the daily – even hourly – news cycle. Ambitious investigative projects and narrative journalism content are not common due to insufficient financial resources and audiences’ preference for the coverage of breaking news. The outlets that offer essays or reviews are dependent on freelancers receiving a very small fee. Sinan Dirlik, founder of the Reportare website, explains the decision to launch a YouTube channel after 10 years of publishing longform text interviews by saying: “We could not stay indifferent to YouTube, since people like watching rather than reading.”

Turkey is heading for general elections in mid-2023. An overwhelming majority of the media leaders interviewed for Project Oasis have voiced their hope for a significant increase in advertising revenue in the case of a political change. Under the given circumstances, it might be safe to assume that digital native media organisations in Turkey need grant funding from international media support and development programmes in the foreseeable future.

Last updated: January 2023

CREDIT FOR STATISTICS: Press Freedom statistics, RSF Press Freedom Index 2022; Internet penetration and population statistics, from Internet World Stats